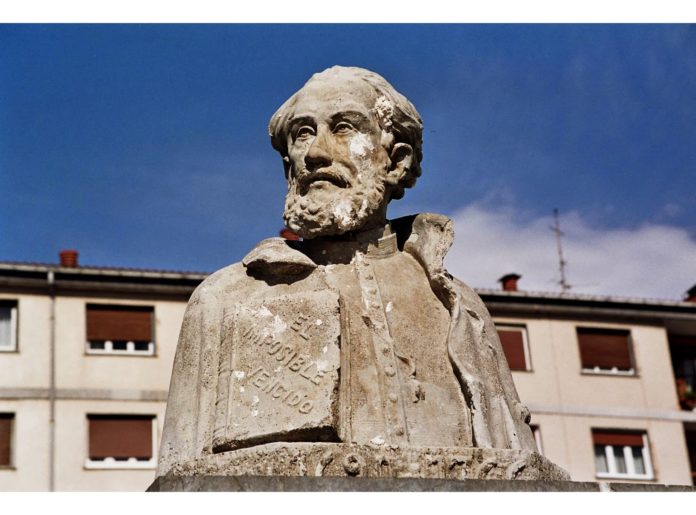

Manuel Larramendi was born on 25 December 1690 in the Garagorri manor farmhouse located in the valley Leizotz, next to the town of Andoain. He was the son of Domingo Garagorri and Manuela Larramendi, and died in Loiola on 29 January 1766 at the age of 76. It is known that he was a member of the Society of Jesus and that in the eighteenth century he made useful contributions to the Basque language, i.e. the first grammar of the Basque language in 1729, El imposible vencido – Arte de la lengua vascongada, and in 1745, the trilingual dictionary Diccionario trilingüe del Castellano, Bascuence, Latín.

These works and others, such as De la antiguedad y universalidad del vascuence en España (1728), Corografía de Guipúzcoa (approx. 1754), Conferencias juridico-político-morales sobre los fueros de Guipúzcoa (approx. 1756), Autobiografía y otros escritos, hold an inherent interest and relevance. Still we will take a focus on the motives and ideas that brought Larramendi to write them. He did not, as we shall see, elaborate them for sheer academic or intellectual purposes, but, above all, encouraged by his affection and passion for his language and his people.

These feelings, which drove him, led him to be an ardent defender of his language and people, and to stand out among the Basque apologists, who saw the identity of the Basques and their laws threatened. He was undeniably fond of controversy, for he had to stand up against both the foes of Basque language and the Basques and domestic indifference.

Larramendi progressed from being a Basque language apologist and theoretician to be a pragmatic linguist, delving into the systematization and normalization of the language. He attempted to prove that Basque language is a full-blown language, and took up its study by writing its grammar: “The drive that has led me to such a complex analysis has not only been to elevate and enlighten our language, but also to give prestige to our Fatherland. Nonetheless, a stronger incentive, more connected to my nature, is the benefit and utility that this work may bring to the whole of the people in the Basque Country, since this language is necessary for the common people, for whom Romance is of little use”. (Foreword of El imposible vencido… – translated from Spanish).

He drew up the dictionary by collecting words of his period and enriching the vocabulary with new words and loans from other languages. As he states in the foreword of his Diccionario…, “now Basque is in a different state, it is instrumental for any science or field. It is high time we looked for the right words it has not treasured so far, borrowing them from other languages or coming up with new ones or making them derive from its rich roots.”(Translated from Spanish).

However, Larramendi’s take on language is not limited to the purely scientific/technical domain, but considers it to be a social phenomenon: language is not merely an ability of the individual, it belongs to a geographical and ethnic community, it stands for a means of identifying a nation or ethnicity, in our case a guarantee of its ancient origin, a differentiating phenomenon.

Since he considers language as an instrument for identifying the nation, he goes even further, to the point of advocating for the creation of a free nation on the basis of its linguistic community: “What reason is there for the Basque nation not to be a separate nation, a natural nation, free and independent of others? Dead languages, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic and others (sic), had each their own nation, governed by themselves, without being subject to any other near or distant nation. Presently, the living languages enjoy the same independence and exception as French, Spanish, and others. Why, therefore, is it that Basque, a living language, being more alive than any other, cannot see all its Basque speakers united and together, as a free nation, outside other languages and nations?” (Fueros, p. 58, translated from Spanish).

From that point of view, he concludes that:

1.- The Basques have the right to express themselves in their own language, and the Castilians must approach the Basques in Basque:

“Isn’t it shameful that they should speak to us, the Basques, in the Basque Country, not in the language intelligible to us all, not in the language of our people, our parents… but in the foreign language of the Castilians?” (Letter to Father Mendiburu)

“… Now leave, use next time my Basque language and speak to me in my way, instead of me having to talk to you in Spanish, you foreigner” (Foreword to the Dictionary).

2.- He also believes that the Basques should not need to know Spanish well, just as the Spaniards are not compelled to be competent in French.

3.- To those who argue that the Basque language is a hindrance to learning Spanish well, he replies that Spanish is a hindrance to learning Basque or any other language that is not related. He therefore puts languages at the same level. The difference consists in the attention paid to each one, and in the prestige assigned to it. He regrets the neglect of his countrymen: “The Basques have not valued their language… The country itself discards the means of protecting it and discovering its finesse” (Prologue of the Dictionary, p. XLVIII – translated from Spanish).

4.- He proclaims the use of the Basque language for all social fields: church, teaching, administration, courts, etc., that is, in all functions relating to a national language: “It is necessary for doctors and surgeons, and lawyers and solicitors in court to be Basque, so that they can understand, attend to and serve all or most of the litigants” (foreword of the Diccionario…, p. CXLVI).

5.- Larramendi described the sociolinguistic situation of his time, stating that “here, Spanish is taught for reading and writing, and children are also prohibited from speaking in Basque for no reason” (foreword of the Diccionario…, p. CXLVI – translated from Spanish). He goes on to denounce what we now call a “diglossic” situation, and defines Spanish language as a regnant language. Spanish is presented as the dominant language in the relations between Basques and Castilians: “A Castilian, hitherto, on hearing just a Basque word, not only does he refuse it, but loathes it, hates it, and much less learns the Basque language” (foreword of the Diccionario…, p. CXCIX – translated from Spanish).

His struggle for the language is closely related to his defence of the territory. Since he hails from Gipuzkoa, his curiosity and interest are primarily directed towards that territory, but he does not adopt any “provincial” approach. He sees Gipuzkoa as a constituent part of the Basque nation and puts it on par with the rest of the provinces. His political ideas are especially summarized in his work Conferencias… In the face of the incoming external aggression, he feels compelled to defend his people, stating that “it is obvious that these conferences are apologetic, they do not oppose writings or papers, but they face up against the dictates and actions of our declared enemies. They are an advocacy for the former liberty of Gipuzkoa and its exceptions, since despite being not guilty, it is being held and bound against its will by means of by violence, ill-treatment, and force.”

He disagrees with the European thought diffused by the Enlightenment under the motto “We are all equal” on the grounds that it leads politically to centralism and absolutism, standing up instead for the singular identity and history of the Basque people. His disagreement lies not so much on the ideas as on their consequences, which he sees as contrary to traditional laws and institutions, called Foruak, and ultimately paving the way to their suppression and the submission to Castile.

Larramendi proclaims the right of resistance to this subjection, and suggests territorial secession. He goes even further in his ideas, proposing a constitution and a new status for the Basque Country. In the lectures compiled in Sobre los Fueros de Guipuzcoa, he clearly expresses his will or dream:

“What are the reasons for the Basque nation, the original inhabitants of Spain, should not be a separate nation, a natural nation, a free and independent nation?” (translated from Spanish).

Since the grounds and foundations of that nation are Basque language, “why is it that Basque, a language as lively as any other, even showing more vitality, cannot see all its Basque speakers united and together, as a nation free of bounds and submission to any other languages and nations?” (translated from Spanish).

Furthermore, he exactly defines the boundaries of that nation in the same way as Sabin Arana outlined them a century later under the name of EUZKADI: “What reason is there for this privileged nation not to be a separate nation, a nation in its own right, a nation exempt from and independent of the others? (…) Why should three provinces of Spain, namely, Gipuzkoa, Alava and Biscay, not to mention the Kingdom of Navarre, be dependent on Castile, and three others, Lapurdi, Zuberoa and Lower Navarre, be dependent on France? Let us request this to them, and we shall call ourselves the United Provinces of the Pyrenees”. (Translated from Spanish).

These are the questions left in the air for us by a groundbreaker, MANUEL LARRAMENDI.

Three centuries on, will we be able to answer and realize his dream?