Jordi Martí Monllau (Tortosa, 1967) is no doubt one of the thinkers who has come up with the clearest thought on the Catalan nation and its language. Philosopher and linguist, collaborator in the digital journal NÚVOL, his writings clearly reflect his profound intellectual commitment to his nation. He attributes great importance to nation-making, to the consolidation of the nation, in order to successfully complete an independence process. “The nation is dying and we are talking about a strategy to achieve a state,” he wrote critically.

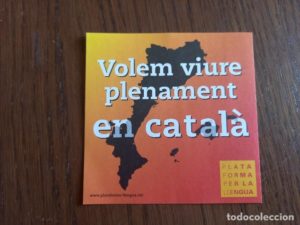

Martí Monllau’s Catalanism is not limited to the four provinces of Catalonia. He holds a global view of the Catalan nation, from the cross-border Catalonia to the south of the “País Valencià”, from the eastern strip of Aragon to the Balearic Islands. The Catalan Countries are, in their entirety, source of study and concern of this philosopher from Tortosa.

Our interviewee lives in Ulldecona, on the southern border of Catalonia, but not of the Catalan Countries. We went there to talk to him, and this interview we are now publishing is the outcome of that long and substantial conversation.

The title of your latest interesting book, which we recommend reading, is “Llengua i identitat nacional” (Language and National Identity). It takes courage nowadays, in times of globalisation and “multiculturalism”, to associate language and identity, even more so when talking about identity is not politically correct and brings you under suspicion. And when non-nationalist independentism relativises the importance of language and national identity …..

Identity is neither good nor bad, it is inevitable. And this identity has two dimensions: psychological (which depends on personal factors) and collective (which depends on the environment). Societies are not merely the sum of their individuals; they are real beings, which go right beyond that sum. The collective dimension of identity becomes a nation when society is united by a number of bonds, both objective (language, culture, history…) and subjective (sense of belonging).

Additionally, we live in the paradigm of nations, that is, the ethical domain in which we live. Therefore the nation is not outside us, but within us, in our collective dimension.

As an indispensable element of material identity, language plays a fundamental role in building national identity, and its role goes beyond being a mere communication device. Language is an instrument of collective identification that channels a culture of its own.

Humans need community to define themselves, because we are social beings, and communities, distinct in many ways as they may be, are always defined by language.

We read that you say that in today’s political systems the citizen is a passive client, who through his vote places political servants in positions of responsibility… But often the people do not have an adequate shepherd. In the current political system, it is obvious that the Catalan and Basque parties often function tactically and in reaction to circumstances. They do not elaborate, neither in specific programmes nor in practice, a strategy to achieve a solid national construction. If we are to base nation-building on identity and language, these circumstancial political responses do not develop a winning strategy. In a scientific way, beyond these parties how can the correct strategy be formulated? How to determine the basic conditions to obtain and stabilise the whole national structure? What would be the best way to get there?

The voter, rather than a passive client (the demos), is now directed at political parties as service companies. “I pay you with my vote, and you give me a service.” After all, the pool of voters firmly believes that political parties are there to solve their problems, and that is a very immature way of thinking, since we all need to solve our problems. This immature mentality is very common in the West. Citizens refuse to take responsibility and relinquish all responsibility to politicians.

As for the second part of the question, the only way to transform reality is to confront it. Overall, this generally leads to conflict, since the strategy of transforming reality requires analytical capacity, recognizing that natural national structures can only be achieved through conflict, and, once the strategy is decided, enforcing it and acting, knowing that nothing guarantees you a victory. All successful national liberation movements have been based on this.

You must understand that you are not fighting for yourself, but for something else that gives you meaning. Perhaps the fruit of your work will be seen only by those who are not yet born, for that is patriotism, the ideology of transcendence. You fight because you want your nation to live on in future generations.

From patriotism comes cosmopolitanism. The first thing to do is to appreciate one’s own country, and from this comes solidarity with other communities. Thus, starting with the country, we can become citizens of the world through a process of enlargement.

From the Basque Country we have always looked on with envy at the linguistic situation in Catalonia. Because Catalan is, among the minoritised languages of Europe, the one in best health and with the most speakers. Lately, however, there have been signs of a weakening of the language, and not a few Catalanists are concerned about the fall in the use of the language. The use of Catalan is falling, and so is the percentage of Catalans who have Catalan as their main language (for example, despite knowing the language, only 19% of young people in Barcelona have it as their main language). What are the reasons for this negative evolution?

Catalan is drowning. We Catalans have not abandoned our own language, but we Catalans are drowning in the face of a demography that is diminishing our chances of living in Catalan.

It is a multifactorial problem. On the one hand, we have been persecuted for centuries, which has brought Catalan monolingualism to an end and has instilled linguistic docility in us (because we almost always speak Spanish in front of Castilian speakers). On the other hand, we have the linguistic influence of demographics: the massive advent of Spanish immigration in the 20th century and the other 2 million immigrants from around the world over the last 25 years have changed their language habits. A third factor is the media, the internet and new technologies, especially those with Spanish content.

Another aspect is that ever more young Catalans are going abroad in search of better employment opportunities, and on the contrary, more and more foreign professionals are coming to Catalonia. Recently, a private company in the field of geriatrics has hired 2,000 nurses from Colombia to work in Catalonia. Those Colombians are going to look after our elders, some of whom get along very badly in Spanish.

You say that the Spanish State has dynamited the legal and juridical defence of the language. Even more, the judiciary itself is active against our languages. The only thing left is the speakers’ capacity for resistance, which is ultimately based on conviction and therefore on the strength of the discourse. Where are the national institutions? Are we speakers alone? What instruments do we speakers need to maintain the language?

Language habits are not free, they do not depend solely on the will of a person. They are social events and are therefore conditioned. The Spanish-speaking ideology always speaks of “freedom of language” in Catalonia, but that freedom does not apply in Castile. In the Spanish state, Castilian speakers do have individual linguistic rights in Catalonia or in the Basque Country, but we do not have those individual linguistic rights when we go to Castile.

Spanish courts are Castilian courts. And when they talk about language issues, they’re partisan, they’re not impartial, because many of them have a dominant Castilian ideology. Faced with this, our institutions have been deactivated to defend the language.

The judges are making language policy. And this is serious, because the judges have not been elected by the people. The government of judges is tyranny. The institutions of our two countries are not free to make the necessary language policies, but they have the opportunity to do something, and we citizens must demand that they do everything they can, and do it intelligently. In addition, both the Basque Country and Catalonia are home to excellent sociolinguists whose advice the institutions should take into account.

Beyond the institutions, each of us can do a lot for our own language, but for that we need our political discourse, strong and elaborate.

In your book you talk about linguistic justice, what is it and how should we demand it?

All human relations are power relations. There is also a relationship of power in language behaviour, which can turn into abuse, which produces injustice.

Justice comes down to giving each one their due; treating the equal as equal and the different as different. Do Catalans, Basques and Castilians deserve the same respect? Of course, and so do their language communities. Therefore, if we deserve the same respect and are equal in this respect, we Catalans and Basques should have the same status in our historical linguistic domain as a Castilian in Cuenca or Seville. If that doesn’t happen, we don’t have language justice.

Are there collective rights, public rights? Of course, since all people also have a collective dimension, and when we talk about collective rights, we mean the rights of individuals (not the rights of a territory), in their collective dimension.

You say that Spanish nationalism has imposed its discourse on us and that, moreover, it has made us accomplices in our national regression. The pro-independence discourse itself has a Spanish influence:

– The claim is limited to the autonomous framework.

– The Spanish language is naturalised and considered as Catalan as Catalan itself.

– The national claim focuses on material and welfare aspects, or on improving governance.

What should we do to replace this harmful discourse with a liberating discourse?

We have come to accept the preconditions of Spanish linguistic nationalism. And by doing so, we are also accepting its discursive and thought frame. For a start, many Catalan independentists only associate the Catalan nation with the four provinces of Catalonia. And our nation is much more, from Salses (Northern Catalonia) to Guardamar (South of the Valencian Community), and from Fraga (Huesca) to Maó (Menorca). Independence must be an instrument for the survival of the nation, but the whole nation. If this does not happen, we shall have to slow down the goal, because the important part is the survival of the whole nation. Our nation is very much disjointed, far more than yours.

As far as the language is concerned, in the years of the independence procès, a movement called SUMATE was formed, consisting of Spanish-speaking independentists, who made pro-independence propaganda in Spanish. Well, that weakens the nation, because Catalan should be everyone’s language of identification, but here there is a great fear of Castilian irredentism, which in turn spurs a justification of bilingualism.

With regards to the “welfare independentism “: Catalan independetism has focused heavily on “food issues”, welfare, and has rejected identity and culture, fearing Spanish irredentism. It has tried to link independence to economic prosperity, setting aside national discourse. This makes no sense, in my opinion, because a pro-independence discourse must be, above all, a national liberation discourse. If the goal is to live well and have more money, let’s do it, but let’s not make a pro-independence speech. If we just aspire to social benefits, we might as well vote for PODEMOS or the Spanish left, we don’t need to be independentists.

Taking language as the axis, the language itself needs an adequate and complete environment, like fish need water, to survive and develop. How would you define this necessary context and its main elements, which according to some theories is characterised as a polysystem of its own? How can we define, as accurately as possible, this polysystem of its own that the Catalan or Basque language needs to survive and develop? How can we complete and develop a cultural polysystem of our own, when we still do not have our own state and we are on the way to achieving it?

We, Catalans and Basques, need a common communication framework in our nations, which is essential for the survival of our languages. In our case, the nation is so disjointed that it is very difficult. We need, for example, shared media for all areas of our country. Today it is not possible to watch TV-3, Catalan television, in the Valencian Country.

We need to create natural ecosystems to normalize the language. In companies, for example, so that it is possible to work only in Catalan; and make Catalan the only language in the interaction between companies and customers, if customers request it. The right of clients to be treated in their language has, by the way, been rejected by the Spanish Constitutional Court. Natural ecosystems are also needed in other areas: audiovisual, digital platforms, etc.

It is undeniable that the large-scale immigration that Catalonia and the Basque Country have received and continue to receive has had a great influence on the situation of our languages. You have mentioned this more than once in your work. On this subject, how should we work on our own discourse, far from the xenophobic positions of the extreme right, which criminalises immigrants, but which at the same time does not hide the influence of demographic movements on our languages and our cultures?

Immigration is never a problem, the problem lies in the context in which it occurs. When an unprotected national minority receives immigration, its effects are very different from those of an independent national majority. At any rate, those who lose most in migration processes are always the societies at the source of migration, since they are deprived of human capital.

The immigration received by the Catalan Countries has been disproportionate. It almost surpasses its population. No society can withstand this in terms of human cohesion. Of course, no independent society, the problem is that we are not independent.

Almost half of the immigration we receive comes with the hegemonic language of the Spanish state, which obviously has negative consequences for Catalan. On the other hand, immigrants have an individual responsibility. We need to explain to migrants the concept of linguistic justice, so that they can respect and learn our language.

The power is in the hands of France and Spain. Given our centuries of subordination, and knowing that these two states seek the disappearance of the Catalan and Basque nations, how do you expect the demand for justice to advance? What must the subjugated people do to achieve the national justice it deserve?

First of all, we need a strong political discourse of our own, and political action. We must not avoid conflict, but it must seek achievable goals without forcing the Spanish state to disappear.

Our peoples are disfigured, and we need, above all, a reconstitution. I believe that at the moment the claim for independence is out of place. Without disdaining it, we must now strive to consolidate the nation. The insistence on independence in Catalonia does not help us achieve the political goals necessary for nation-making, and it only leads to frustration. I am aware that my speech is frowned upon by many independentists and that I will be subject to criticism for this, but this is my opinion. I, above anything else, want to die being Catalan, just as I was born.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY NAZIOGINTZA

JULY 2023